The Story:

Sam and I were on our second day of five day long traverse across all of the nine 12,000’ peaks of Idaho. They fall within three different mountain ranges and involve car shuttles and long drives to connect them this time of year. The previous day we were able to summit Diamond Peak (12,202’) in the Lemhi range and Lost River Peak (12,078’) in the Lost River range. We didn’t get into camp until around 10pm and get to sleep until 11pm. We decided to sleep in until 6am, so we would have more energy for the next day which included tagging Mount Breitenbach, Donaldson, and Church. We acknowledged that by leaving later in the morning (instead of waking up at 4am), we would be more exposed to the solar input of the snowpack during the middle of the day while skinning up southerly aspects.

As we moved through the day, our bodies were feeling decent, but I mentally felt exhausted. This was the result of stormy conditions and challenging decision making from the previous day. We skied off Lost River Peak in the dark with headlamps and found our previous ski line (Squiggly Wiggly) was guarded by a massive cornice. Although the chance of this releasing at that moment was highly unlikely, I wasn’t ready to accept that risk of being in a tight couloir and directly in the line of fire. So we decided to put skins on and climb higher on the ridge to where we remembered some couloirs that went free without cliffs in them. I felt like we were Mary and Joseph (prepare for weird reference) being denied an inn to stay in for the night, as we moved from couloir to couloir until we finally found that barn to lay our heads down… anyways it was a long day.

Sam and I were on our second day of five day long traverse across all of the nine 12,000’ peaks of Idaho. They fall within three different mountain ranges and involve car shuttles and long drives to connect them this time of year. The previous day we were able to summit Diamond Peak (12,202’) in the Lemhi range and Lost River Peak (12,078’) in the Lost River range. We didn’t get into camp until around 10pm and get to sleep until 11pm. We decided to sleep in until 6am, so we would have more energy for the next day which included tagging Mount Breitenbach, Donaldson, and Church. We acknowledged that by leaving later in the morning (instead of waking up at 4am), we would be more exposed to the solar input of the snowpack during the middle of the day while skinning up southerly aspects.

As we moved through the day, our bodies were feeling decent, but I mentally felt exhausted. This was the result of stormy conditions and challenging decision making from the previous day. We skied off Lost River Peak in the dark with headlamps and found our previous ski line (Squiggly Wiggly) was guarded by a massive cornice. Although the chance of this releasing at that moment was highly unlikely, I wasn’t ready to accept that risk of being in a tight couloir and directly in the line of fire. So we decided to put skins on and climb higher on the ridge to where we remembered some couloirs that went free without cliffs in them. I felt like we were Mary and Joseph (prepare for weird reference) being denied an inn to stay in for the night, as we moved from couloir to couloir until we finally found that barn to lay our heads down… anyways it was a long day.

Back to the second day… we moved up through Dry Creek and noticed the winds were sending lots of spindrift over the walls of the rock faces around us. We talked about how wind slabs would be a concern as we moved up into higher terrain and that the blue skies would eventually trigger some loose wet avalanches. As we approached our first climb to Mount Breitenbach, we could see the face was looking more barren than last year. It was because it had ripped out in the late February cycle, probably as a D3 deep persistent slab. This was evident with the large debris piles at the base with a month’s snow sitting on top of them.

We were able to skin the whole way up the face. We triggered a few small wind slabs that were mid slope and failed 3-5” down x 10’ wide. The hard part about traversing through the Lost River range is that it’s nearly impossible to stay out of avalanche terrain, unless you stick only to ridgelines, which then makes no sense to be carrying skis. We were able to make it to the summit of Breitenbach (12,140’) without significant problems. I looked around for signs of recent avalanches, thinking there must be something out there with the 4-8” of light density snow and moderate to strong NW winds. I saw nothing. After digging out the summit registry, we descended the west face of Breitenbach in epic powder conditions.

We were able to skin the whole way up the face. We triggered a few small wind slabs that were mid slope and failed 3-5” down x 10’ wide. The hard part about traversing through the Lost River range is that it’s nearly impossible to stay out of avalanche terrain, unless you stick only to ridgelines, which then makes no sense to be carrying skis. We were able to make it to the summit of Breitenbach (12,140’) without significant problems. I looked around for signs of recent avalanches, thinking there must be something out there with the 4-8” of light density snow and moderate to strong NW winds. I saw nothing. After digging out the summit registry, we descended the west face of Breitenbach in epic powder conditions.

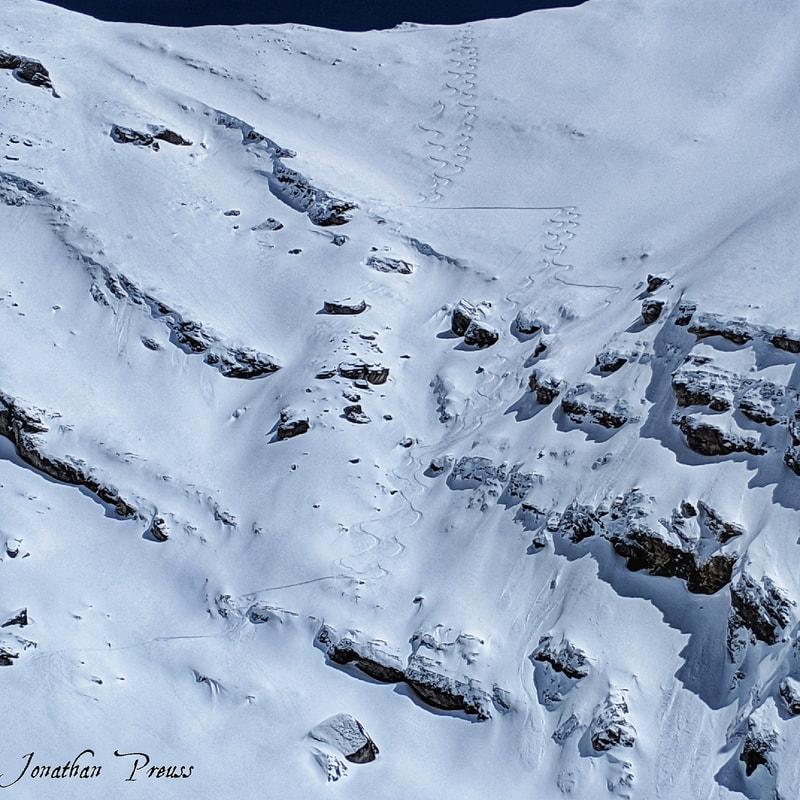

Sam approaching the ridge line, right before we triggered the avalanche. Donaldson Peak is in the background.

Sam approaching the ridge line, right before we triggered the avalanche. Donaldson Peak is in the background. When we got to the bottom, we transitioned to go up our normal ascent path of Mount Donaldson via the Southeast bowl to the Northeast ridge. We noted how we felt like we were traveling across the Sahara desert. The winds calmed down in that basin and it was accelerating the solar input on those bowls. There were loose wet slides coming down the Fishbone couloirs off Donaldson, so it seemed to make sense to stay away from that hazard. It also allowed us to avoid the slopes that were starting to take solar gain from the sun in the SW part of the sky. We saw a recent D1 pocket rip out from behind a rib, mid way up the skinner’s left. It looked like a cross loaded feature and verified our thoughts on the possibility of wind slabs. We discussed our plan for attack was to avoid getting close to the ribs (to avoid cross loaded wind slabs) and stay on the planar and fattest part of the slope. It also was the lowest angle approach to the ridge, varying from 30-40°, the steepest part was the last 200’ vertical.

When I’m out on these personal trips, I’m willing to take on more risk. That risk includes skiing steeper and more consequential terrain (such as skiing above cliffs, steep couloirs, and traveling in big basins). That’s not to say I’m ready to die in the mountains, I’m just accepting that it is a dangerous place and things can happen out there. I’m willing to put myself in it for the personal growth that comes from completing endeavors that seem nearly impossible on the drawing board. Whereas when I’m working as a mountain guide, I’m not willing to put my guests into that type of terrain without having very good stability in the snowpack and using the application of ropes to lower exposure over complex terrain.

When I’m out on these personal trips, I’m willing to take on more risk. That risk includes skiing steeper and more consequential terrain (such as skiing above cliffs, steep couloirs, and traveling in big basins). That’s not to say I’m ready to die in the mountains, I’m just accepting that it is a dangerous place and things can happen out there. I’m willing to put myself in it for the personal growth that comes from completing endeavors that seem nearly impossible on the drawing board. Whereas when I’m working as a mountain guide, I’m not willing to put my guests into that type of terrain without having very good stability in the snowpack and using the application of ropes to lower exposure over complex terrain.

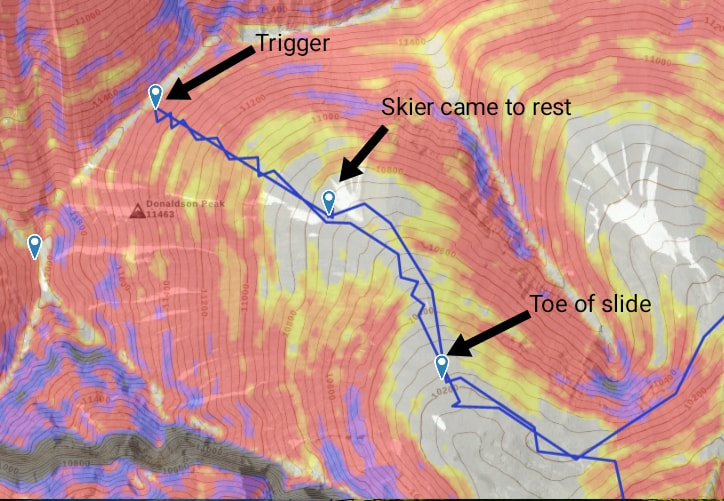

Gaia GPS track of our route towards Donaldson Peak, involving the avalanche.

Gaia GPS track of our route towards Donaldson Peak, involving the avalanche. Sam started up the SE bowl, setting a beautiful skintrack with gradual switch backs, avoiding the ribs to each side of us. We were feeling hot and tired, the previous day was starting to present itself in the form of fatigue. I did a couple of pole pokes and felt various layers in the upper pack with basal facets or depth hoar at the bottom. The snowpack seemed typical for the Lost Rivers, which is notorious for shallow snow and depth hoar. Height of snow was 100-120cm (anyone notice where this is going?). As we approached the ridgeline, I gave Sam even more space between us. The snow didn’t feel like it was wind loaded, it was moist (2-3”) and was sitting on top of some sort of melt/freeze crust.

Sam was about 20’ below the ridge, when I heard it… the familiar sound that makes the hair stand up on your back. WHUMPF. It sounded like two collapses, one sounded like a deep rumbling, while the other was lighter and more shallow. I instantly dropped to my knees to punch the toe pieces out of being locked. I managed to get my right ski off. Remember we were ascending, this is the worse situation to be in when caught in an avalanche, because you are the most vulnerable when going up. I teach in my avalanche courses to minimize exposure on the uphill where we spend most of our time ski touring. This lowers the chance of being caught in an avalanche - but we didn’t have those safer options.

I saw the slope fracture and shatter like a pane of glass all around me. I remember saying to myself, this is it, this thing is breaking to the ground. If you want to live, you have to do everything you can to fight to stay on top. You're not going out like this. Adrenaline filled my body as I started to pick up speed and accelerated down the slope. I was lying face down with my left ski still attached and trying to drag me down, deeper into the debris. I started doing push ups off the blocks of snow to try and stay as close as I could to the top of the debris. It felt like being on a water slide, I could feel all the undulations of the mountain as I was carried over them. With the debris being as hard as it was, I didn’t experience any choking from snow getting pushed down my throat. As I felt the debris start to slow down, I forced myself to work harder in order to increase my chances of coming out on top. It worked. As I tried to pull myself out of the snow, my right arm was stuck. I jerked it until it became free, leaving my glove stuck in the snow. I still had my left ski attached to me and had to unbuckle my pack to get turned over. My initial thoughts were, what if that sympathetically released the Fishbone Couloirs and I was right in their path. I looked around, all was still. My next thought was, is Sam ok? I quickly looked upslope and saw he was able to self arrest and stay on top of the upper bed surface. He was glissading down to his skis and I signaled up that I was ok. I double checked myself to confirm that I wasn’t injured by feeling my arms and legs for bumps, knowing that I was still filled with adrenaline and that sometimes injuries go unnoticed.

Sam was about 20’ below the ridge, when I heard it… the familiar sound that makes the hair stand up on your back. WHUMPF. It sounded like two collapses, one sounded like a deep rumbling, while the other was lighter and more shallow. I instantly dropped to my knees to punch the toe pieces out of being locked. I managed to get my right ski off. Remember we were ascending, this is the worse situation to be in when caught in an avalanche, because you are the most vulnerable when going up. I teach in my avalanche courses to minimize exposure on the uphill where we spend most of our time ski touring. This lowers the chance of being caught in an avalanche - but we didn’t have those safer options.

I saw the slope fracture and shatter like a pane of glass all around me. I remember saying to myself, this is it, this thing is breaking to the ground. If you want to live, you have to do everything you can to fight to stay on top. You're not going out like this. Adrenaline filled my body as I started to pick up speed and accelerated down the slope. I was lying face down with my left ski still attached and trying to drag me down, deeper into the debris. I started doing push ups off the blocks of snow to try and stay as close as I could to the top of the debris. It felt like being on a water slide, I could feel all the undulations of the mountain as I was carried over them. With the debris being as hard as it was, I didn’t experience any choking from snow getting pushed down my throat. As I felt the debris start to slow down, I forced myself to work harder in order to increase my chances of coming out on top. It worked. As I tried to pull myself out of the snow, my right arm was stuck. I jerked it until it became free, leaving my glove stuck in the snow. I still had my left ski attached to me and had to unbuckle my pack to get turned over. My initial thoughts were, what if that sympathetically released the Fishbone Couloirs and I was right in their path. I looked around, all was still. My next thought was, is Sam ok? I quickly looked upslope and saw he was able to self arrest and stay on top of the upper bed surface. He was glissading down to his skis and I signaled up that I was ok. I double checked myself to confirm that I wasn’t injured by feeling my arms and legs for bumps, knowing that I was still filled with adrenaline and that sometimes injuries go unnoticed.

We then compiled a plan for getting out of there. Jones Creek was the most obvious escape route. It is known for a heinous exit, lots of bushwhacking and would put us away from our car. Luckily we had a team tracking our every move. Sam became a member of the Gauge 20 Running team, who helped him train for this project. Paul Lind, the lead coach of Gauge 20, lives in Challis and was messaged via inReach that we would need an extraction. Then we skied down looking for my other ski which was near the surface of the snow, 30’ below where I came to rest. Having the second ski would make the exit out Jones a lot easier, compared to the alternative which would require me to switch the one ski between each leg.

As we got down lower, we were able to get cell service and call our wives (Michele and Molli) to tell them what happened and that we were both ok. Jones Creek is a total V trap, and I had concerns of traveling under the west slopes that were just starting to take heat from the sun. But it was our only good option, when compared to spending the night and waiting until the snowpack locked up again. We traveled quickly through old avalanche debris and watched as roller balls were starting to make their way down the slopes. After we made it through the overhead hazards, we just had to link snow fields through a narrow drainage and eventually switched to walking. Our ride was still a couple of hours out, so we made a campfire down in the foothills and brewed up some coffee. We sat around the fire, discussing all the possible errors we made while it was still fresh in our heads.

I wanted to be transparent about the mistakes that we made and hopefully it can aid others to not fall into the same traps. Often when people get caught in avalanches, they are ashamed for the mistakes that they made, and therefore they choose to not report them. We should take ownership and share these stories, so they became lessons in a place [mountains] that is so dynamic and ever-changing in a minutes notice. Sometimes the mountains don’t always give us the feedback we crave.

Thank you to everyone who reached out to me to talk about it and the friends that were happy to hear we weren’t hurt or injured. I’m grateful to live in a community that cares about my well-being. I gained a lot of valuable lessons from this close call and now the signs that I missed are clear. Most were part of the human factor, but others were present in the snowpack.

Reflection:

Our thoughts are that Sam initiated the upper persistent slab (resembling a storm slab) when he was approaching the ridgeline where the slab was thinner. It propagated nearly 1400’ across the slope and stepped down into the basal facets/depth hoar and released a deep persistent slab. The upper crown had a uniform depth and was razor sharp across the slope. Therefore did not present as a typical wind slab. It appeared more like a persistent slab that might have failed on a near surface facet/crust combo. The recent NW wind loading, 0.5” SWE, and/or solar input was enough to make the slab reactive.

We are both incredibly grateful to be alive and uninjured. We put ourselves in a dangerous situation by failing to properly investigate the snowpack in a remote area. The initial avalanche was likely some kind of shallow persistent slab that we were unaware of and had enough force to trigger the deeper persistent slab. We probed and felt the persistent slab, but didn’t test its energy. Had we dug an actual snow pit on this aspect, the likelihood of triggering a persistent slab avalanche would have been very evident. Doing this was even more important since we were in an area with an unknown snowpack. We would like to think that we would have chosen to abandon our objective for that day if we had realized and acknowledged that a persistent avalanche problem existed.

Lessons Learned:

Questions:

If you were able to read all the way to here, thank you for taking the time to look into this close call!

As we got down lower, we were able to get cell service and call our wives (Michele and Molli) to tell them what happened and that we were both ok. Jones Creek is a total V trap, and I had concerns of traveling under the west slopes that were just starting to take heat from the sun. But it was our only good option, when compared to spending the night and waiting until the snowpack locked up again. We traveled quickly through old avalanche debris and watched as roller balls were starting to make their way down the slopes. After we made it through the overhead hazards, we just had to link snow fields through a narrow drainage and eventually switched to walking. Our ride was still a couple of hours out, so we made a campfire down in the foothills and brewed up some coffee. We sat around the fire, discussing all the possible errors we made while it was still fresh in our heads.

I wanted to be transparent about the mistakes that we made and hopefully it can aid others to not fall into the same traps. Often when people get caught in avalanches, they are ashamed for the mistakes that they made, and therefore they choose to not report them. We should take ownership and share these stories, so they became lessons in a place [mountains] that is so dynamic and ever-changing in a minutes notice. Sometimes the mountains don’t always give us the feedback we crave.

Thank you to everyone who reached out to me to talk about it and the friends that were happy to hear we weren’t hurt or injured. I’m grateful to live in a community that cares about my well-being. I gained a lot of valuable lessons from this close call and now the signs that I missed are clear. Most were part of the human factor, but others were present in the snowpack.

Reflection:

Our thoughts are that Sam initiated the upper persistent slab (resembling a storm slab) when he was approaching the ridgeline where the slab was thinner. It propagated nearly 1400’ across the slope and stepped down into the basal facets/depth hoar and released a deep persistent slab. The upper crown had a uniform depth and was razor sharp across the slope. Therefore did not present as a typical wind slab. It appeared more like a persistent slab that might have failed on a near surface facet/crust combo. The recent NW wind loading, 0.5” SWE, and/or solar input was enough to make the slab reactive.

We are both incredibly grateful to be alive and uninjured. We put ourselves in a dangerous situation by failing to properly investigate the snowpack in a remote area. The initial avalanche was likely some kind of shallow persistent slab that we were unaware of and had enough force to trigger the deeper persistent slab. We probed and felt the persistent slab, but didn’t test its energy. Had we dug an actual snow pit on this aspect, the likelihood of triggering a persistent slab avalanche would have been very evident. Doing this was even more important since we were in an area with an unknown snowpack. We would like to think that we would have chosen to abandon our objective for that day if we had realized and acknowledged that a persistent avalanche problem existed.

Lessons Learned:

- There are widespread persistent slabs present on multiple aspects and various depths in the Lost River Range. Most need a medium sized loading event or need to be sympathetically released to step down into deeper persistent slabs.

- When going into a remote range, we should have dug and assessed stability more frequently in the field. Hand pits could have shown the persistent weak layer in the upper snowpack and could have assessed the shear strength. Measuring the potential for propagation could have told us whether to call off our trip.

- It pays to know how to self-rescue yourself in an avalanche. By being quick to kick and pop off our skis, we weren’t buried as deep as we could have been. When lying face down on the slab (and can’t flip over on your back), push off hard debris to help stay on top.

- We should have treated this snowpack with an assessment mindset instead of assuming we were skiing a spring diurnal snowpack based on the time of year.

- Recent avalanches weren’t helpful in evaluating avalanche hazard in our case. When we got to the top of Breitenbach, we could see a lot of terrain on aspects similar to where we triggered the slide, but there was no natural activity. We found out later there were other natural slides near Borah that were similar to the one we triggered, but on a NE aspect which shows it wasn't isolated to only southerly slopes.

- Being alert to only two avalanche problems that day blinded us from being alert to other potential problems (such as persistent slabs). We had discussed and believed the primary avalanche problems that day were wind slabs and loose avalanches. This was due to observing them in the field and seeing a lot of wind transport. Therefore, knowing we were not traveling on a wind slab gave us a false sense of security.

- Having GPS tracking devices on all traveling people in the group is vital. Sam had an InReach and JP had a SPOT. These devices allowed us to communicate with an outsider to come pick us up, and to notify loved ones that we were safe.

- We had decision fatigue, from our previous long day and were not adding up all the subtleties.

Questions:

- Did we remote trigger the deep persistent slab which pulled into the upper slab? This is based on the deep, rumbling collapse I heard at the top of the slope. It seems unlikely that was the case, because why didn’t that deep layer fail all the way up to our location after triggering the collapse?

- Had the deep persistent slab ripped all the way to the ridge, would I have had the same success of staying on top and not get buried?

- Did the influence of the sun have an effect on changing the slab properties and cause that upper slab to fail and propagate?

- Should we have traveled up the steep slopes of the Fishbone Couloirs where loose wet slides didn’t step down into anything? But then we would still have to cross more SE bowls in the days to follow.

If you were able to read all the way to here, thank you for taking the time to look into this close call!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed