It was my third day out in the Mushroom Ridge area. I was feeling confident that I knew what was going on in the snowpack. A couple of waves had brought new snow to the mountains after a three month long dry spell. This time of year people break out their bikes and load up the summer wax on the skis. Meanwhile it was dumping cold snow in the mountains! I love getting out this time of year and skiing steep lines. Although, the new dry snow can change to mash potatoes within minutes, so it's necessary to have a flexible schedule to get the goods.

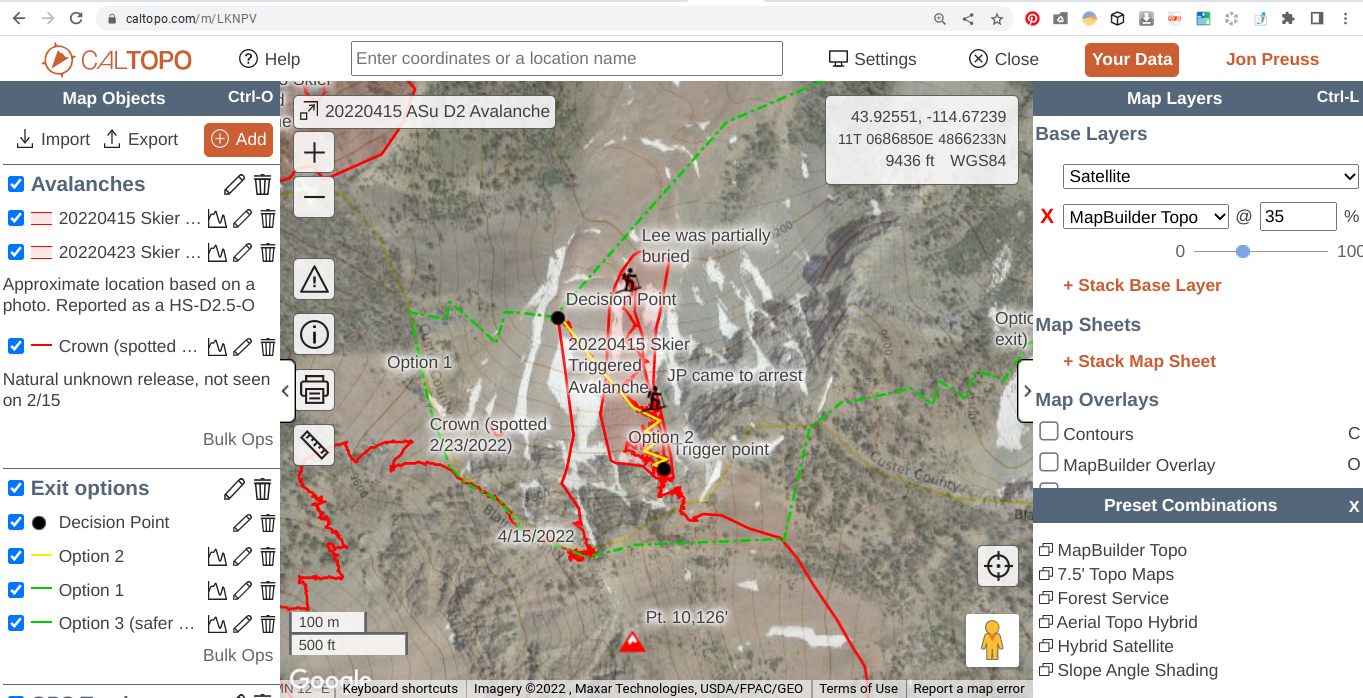

I put out a desperate message attached with some powder photos from the day before to an Instagram post. “Hit me up if you want to ski tomorrow!” An old friend reached out who I haven’t skied with in a long time. I told him to bring all the sharp things he owned and meet at my place. Lee showed up and I opened my laptop with a proposed ski tour I plotted on CalTopo. One couloir that would give us access to the area referred to as Gnaria and then climb back out, traverse a ridge to a north facing couloir. He looked at me and said, “This is exactly what I wanted to do today.” I pointed out three possible exits (refer to CalTopo map with the “Exit Options” folder) from our last run, which would bring us out of the Grand Prize drainage.

Side Note: I put together an interactive map to follow along this story and observations. It was built through CalTopo and there are a bunch of different Map Layers you can toggle through to see Slope Shading (avalanche terrain), Satellite (to see the ski runs), and Mapbuilder (topography lines) to see the terrain features, aspects, and elevations. You can use the folders located on the left to turn on/off (click the arrow in the box) tracks, exit options, etc. which will allow you to focus on one part at a time. Sometimes it can be overwhelming to have everything on the map at once, so you can enable what you would like to see on it. It is best to view through a web browser via laptop or desktop platform and not on the app with your smartphone.

I put out a desperate message attached with some powder photos from the day before to an Instagram post. “Hit me up if you want to ski tomorrow!” An old friend reached out who I haven’t skied with in a long time. I told him to bring all the sharp things he owned and meet at my place. Lee showed up and I opened my laptop with a proposed ski tour I plotted on CalTopo. One couloir that would give us access to the area referred to as Gnaria and then climb back out, traverse a ridge to a north facing couloir. He looked at me and said, “This is exactly what I wanted to do today.” I pointed out three possible exits (refer to CalTopo map with the “Exit Options” folder) from our last run, which would bring us out of the Grand Prize drainage.

Side Note: I put together an interactive map to follow along this story and observations. It was built through CalTopo and there are a bunch of different Map Layers you can toggle through to see Slope Shading (avalanche terrain), Satellite (to see the ski runs), and Mapbuilder (topography lines) to see the terrain features, aspects, and elevations. You can use the folders located on the left to turn on/off (click the arrow in the box) tracks, exit options, etc. which will allow you to focus on one part at a time. Sometimes it can be overwhelming to have everything on the map at once, so you can enable what you would like to see on it. It is best to view through a web browser via laptop or desktop platform and not on the app with your smartphone.

There are no daily avalanche forecasts delivered this time of year, so it becomes even more important to stay on top of the weather and see what is going on in the snowpack. I mentioned to Lee that the best snow right now was on the north faces (as per usual) and the only stability concern I had was Wind Slabs and Dry Loose problems. My thought was to stick to confined terrain features (couloirs), where a precise slope cut could clear away any issues. I wanted to steer clear of big, open faces where it’s harder to safely manage wind slab problems.

At the trailhead we talked about who would carry rescue equipment, first aid kits, bivy tarps and repair kits. Then we separated gear between us to travel light and fast. I mentioned where my inReach device was kept and how to use it. This is something I do with anyone I don’t tour with on a regular basis, especially my guests I’m taking out for the day. We did a transceiver check and marched up the skintrack.

Lee made an observation of the drifting snow once we got higher on the ridge. The winds had basically moved snow from most aspects within the last week, so it was challenging to know exactly where the most recent load was coming from. It was going to require looking at each slope individually to assess where or if it was loaded with any new wind transport. There were no recent slab avalanches observed.

We made it to the top of Mushroom ridge, where we had to do a series of navigating through small bands of rock and snowfields. I poked my pole through the snow to feel if there were any slabs sitting over weak layers. Nothing stood out in my rudimentary stability tests. I elected to downhill skin across the small start zone (~50’ long) to avoid multiple transitions. Looking back on it now, it would have been much safer to stick to the ridge and not add too much time.

We stood at the top of the first run, a 35°+ NNW couloir that had multiple sections to regroup on the way down. I set a slope cut down to a nice moat that was created over the season with the prevailing NW winds. Then continued down fast snow that had pockets of wind-blown pillows to add some softer turns. Nothing moved and I yelled up to Lee to come down to me. He skied down and then continued down the last pitch into the aprons. Just as he started to descend, a local couple were skiing down from the Upper Gnarnia basin. I shouted to him that there was another skier, but he couldn’t hear me. I don’t like dropping in above other parties. It’s bad practice in my mind. If we were to trigger an avalanche, it would be on top of them and possibly add more people buried. Everything was fine and we skinned up to look at our next climb.

At the trailhead we talked about who would carry rescue equipment, first aid kits, bivy tarps and repair kits. Then we separated gear between us to travel light and fast. I mentioned where my inReach device was kept and how to use it. This is something I do with anyone I don’t tour with on a regular basis, especially my guests I’m taking out for the day. We did a transceiver check and marched up the skintrack.

Lee made an observation of the drifting snow once we got higher on the ridge. The winds had basically moved snow from most aspects within the last week, so it was challenging to know exactly where the most recent load was coming from. It was going to require looking at each slope individually to assess where or if it was loaded with any new wind transport. There were no recent slab avalanches observed.

We made it to the top of Mushroom ridge, where we had to do a series of navigating through small bands of rock and snowfields. I poked my pole through the snow to feel if there were any slabs sitting over weak layers. Nothing stood out in my rudimentary stability tests. I elected to downhill skin across the small start zone (~50’ long) to avoid multiple transitions. Looking back on it now, it would have been much safer to stick to the ridge and not add too much time.

We stood at the top of the first run, a 35°+ NNW couloir that had multiple sections to regroup on the way down. I set a slope cut down to a nice moat that was created over the season with the prevailing NW winds. Then continued down fast snow that had pockets of wind-blown pillows to add some softer turns. Nothing moved and I yelled up to Lee to come down to me. He skied down and then continued down the last pitch into the aprons. Just as he started to descend, a local couple were skiing down from the Upper Gnarnia basin. I shouted to him that there was another skier, but he couldn’t hear me. I don’t like dropping in above other parties. It’s bad practice in my mind. If we were to trigger an avalanche, it would be on top of them and possibly add more people buried. Everything was fine and we skinned up to look at our next climb.

The upper basin was wind blown off the ridges and looked like terrible boot packing conditions. We decided it would be best to continue down and then wrap around the ridge to gain pt. 10,126’. There was another small couloir feature to connect us downhill. It was a short, north facing feature that I entered with caution. I skied to the rib in the middle and posted up to have “eyes on” Lee as he skied through the whole pitch. When I can’t see the whole descent, I will try to get down to a safe location so I can see the entire line. In the event it slides, you can see the rider and get a last-point-seen location. It was another solid run with even more ski pen (aka deep snow) thus more powder shots!

The next climb was up a steep west face that connected to a ridgeline. We skinned up it and got a view of our previous two runs. Another party of two were skinning out a wide couloir feature back to the Horse Creek exit (refer to “Other Party of 2” GPS track). The slope was 35-45° (based on Slope Shading) and N/NW facing 9200-9500’. I must have subconsciously acknowledged they were moving through steep terrain with no consequences. This undoubtedly created a bias for the day about stability being good.

We finally got up to the last couloir of the day and this is the one I had been drooling over on Google Earth for a week now. I knew it was going to ski great because I skied a similar feature 4 days earlier and there was more snow out there now. But when we got to the ridge to look into the slope, it was riddled with cornices and the entrance looked too rocky to descend from the top. I looked for another way to access the run. I ran up and down to get different views, looking for a weakness in the corniced ridgeline. There was a small entrance that had a little cornice that we could cut loose with a sawing motion using a ski. Then a small, delicate traverse that would require walking over lots of rocks to get the couloir. I proposed the plan to Lee; he was game for it. So we went to work, carefully turning our way into the run and across the face.

The next climb was up a steep west face that connected to a ridgeline. We skinned up it and got a view of our previous two runs. Another party of two were skinning out a wide couloir feature back to the Horse Creek exit (refer to “Other Party of 2” GPS track). The slope was 35-45° (based on Slope Shading) and N/NW facing 9200-9500’. I must have subconsciously acknowledged they were moving through steep terrain with no consequences. This undoubtedly created a bias for the day about stability being good.

We finally got up to the last couloir of the day and this is the one I had been drooling over on Google Earth for a week now. I knew it was going to ski great because I skied a similar feature 4 days earlier and there was more snow out there now. But when we got to the ridge to look into the slope, it was riddled with cornices and the entrance looked too rocky to descend from the top. I looked for another way to access the run. I ran up and down to get different views, looking for a weakness in the corniced ridgeline. There was a small entrance that had a little cornice that we could cut loose with a sawing motion using a ski. Then a small, delicate traverse that would require walking over lots of rocks to get the couloir. I proposed the plan to Lee; he was game for it. So we went to work, carefully turning our way into the run and across the face.

After some debate on whether we were skiing or rock climbing, we were in! We skied it in two pitches, regrouping halfway down. It was all time skiing and we wished it lasted for another 1000’ or even more. At the bottom, we looked back up and talked about the run. We discussed our exit plan out of there where I again brought up all three exit strategies (refer to the “Exit Options” folder) in no particular order.

Refer to the CalTopo interactive map to fully understand the following options.

Option 1 was to exit through a small, steep section that looked wind loaded and would require gaining the same ridge we had just walked up. That ridge sucked! Lots of booting over loose rock---we quickly said no to that option.

Option 2 was to gain the saddle next to where we ended the run. It was a small face with a 200’ band of red (35-45° slope shading). This was the fastest way out and that definitely was calling our names.

Option 3 was to continue down the basin and wrap around through lower angle terrain. It was the longest way back to the Western Home exit, but by far the safest. The steepest section of this route would be on an East aspect, which was less likely to have any avalanche problems on it with recent sun exposure.

We talked over all of the options and our tired bodies kept going back to Option 2. We had a great day and we were now “smelling the barn.” When analyzing skin tracks in avalanche terrain, there are a few points I take into consideration. These are to be taken into account, if there is no other safer option to move through that terrain. In other words, you have to go up through steeper slopes.

I started to break trail up the exit Option 2 (marked in yellow) towards the saddle that would give us a fast exit back to our vehicle. We were halfway up it and I looked back at Lee and asked if we should ski another run down the skintrack. We agreed it would be great snow, but would make the decision at the top.

Option 1 was to exit through a small, steep section that looked wind loaded and would require gaining the same ridge we had just walked up. That ridge sucked! Lots of booting over loose rock---we quickly said no to that option.

Option 2 was to gain the saddle next to where we ended the run. It was a small face with a 200’ band of red (35-45° slope shading). This was the fastest way out and that definitely was calling our names.

Option 3 was to continue down the basin and wrap around through lower angle terrain. It was the longest way back to the Western Home exit, but by far the safest. The steepest section of this route would be on an East aspect, which was less likely to have any avalanche problems on it with recent sun exposure.

We talked over all of the options and our tired bodies kept going back to Option 2. We had a great day and we were now “smelling the barn.” When analyzing skin tracks in avalanche terrain, there are a few points I take into consideration. These are to be taken into account, if there is no other safer option to move through that terrain. In other words, you have to go up through steeper slopes.

- Is there a persistent slab problem? If the answer is NO, then proceed with caution. Dig to visually verify and periodically check to confirm throughout the climb out. Other avalanche problems should be considered too.

- Stay on the lowest slope angle as possible. Statistically speaking, the closer you get to the magic number of 39°, the more likely the slope is able to trigger an avalanche. If there is a collapse in a layer, it will travel faster and possibly longer in steeper terrain. Thus creating a larger avalanche with more snow to knock you over or get buried deeper.

- Stick to the deepest snowpack or no snow at all. I’m sure this point will open up some discussion. Some would argue if you are thinking in this manner, then maybe you shouldn’t be on that slope. Thinner snowpacks are notorious for being trigger points in avalanches. We are traveling and impacting the snow closer to that layer and more likely to initiate the failure. So if you stick to the deeper snowpack, you are less likely to trigger anything sitting below in the snowpack. But if you do trigger an avalanche, it will likely be a hard slab which is more destructive and challenging to get off. It is always safer walking up on rock, where you aren’t connected to the snowpack. But it is slower and less efficient to carry your skis/boards on your back. Keep in mind that traveling over little sections of snow, that are connected to bigger slopes, can be ideal spots to trigger avalanches as well.

- Avoid being over terrain traps (gullies, cliffs, creeks). Make sure it has a clean runout in case it were to avalanche. Slopes that gradually change to lower angle will allow debris to “fan out” and not bury you as deep. Therefore, it increases your chances of staying on top if caught in an avalanche.

- Are there any environmental factors increasing the chances of causing injury? Is the sun influencing slab consolidation or introducing water into the snowpack to cause Wet Loose or Slab avalanches? Is there rock or cornice fall from above and could we be in the line of fire?

I started to break trail up the exit Option 2 (marked in yellow) towards the saddle that would give us a fast exit back to our vehicle. We were halfway up it and I looked back at Lee and asked if we should ski another run down the skintrack. We agreed it would be great snow, but would make the decision at the top.

I was about a switchback away from being in the clear and standing at the top, when I saw snow moving all around me. I remember thinking, “Fuck, not again.” I somehow turned myself around and tried to run over (we were in tour mode) towards the flank of the slab. After I fell over on my side, I knew I was in it and reached for the trigger on my avalanche airbag. I could hear it inflate the large red balloon around my back as I tried to push to keep myself on top of the debris. I came to a rest on the bed surface and looked up to see what was above me and see if I could see Lee. Then I looked down to see the slide was continuing down the mountain and I could see Lee on top near the bottom. Everything came to a rest and I shouted down, “Are you alright? Do you need help getting out?” I could see he was on top and only partially buried, so I ripped off my skins and skied down to him.

We were in awe of what just happened. I remember being angry that I just got caught in another slide within 3 years almost to the day. I felt “like a boxer that's been knocked down and lost his step” - Senses Fail. How did I let that happen again?! Then I couldn’t understand why I felt so calm. The first slide I was in I thought, "I could die in this right now." But why didn’t I feel the same rush of adrenaline with this one? Was it because I didn’t hear the collapse or that I could feel the floor of the bed surface and knew it wasn’t too deep? I knew the runout was clean and a good place to get caught. It was a strange feeling.

We were in awe of what just happened. I remember being angry that I just got caught in another slide within 3 years almost to the day. I felt “like a boxer that's been knocked down and lost his step” - Senses Fail. How did I let that happen again?! Then I couldn’t understand why I felt so calm. The first slide I was in I thought, "I could die in this right now." But why didn’t I feel the same rush of adrenaline with this one? Was it because I didn’t hear the collapse or that I could feel the floor of the bed surface and knew it wasn’t too deep? I knew the runout was clean and a good place to get caught. It was a strange feeling.

Lee was only buried knee deep and right side up, so he was able to wiggled his way free. We talked about the slide and walked through the chain of events. Lee remembered us both shouting avalanche, when I only remember looking at him right before my trauma response went into fight (beast) mode. He heard the collapse when I didn’t hear anything. I remember getting a bad feeling maybe 30 seconds or so before triggering the avalanche.

I have thought back on that feeling a lot since that day. What could I have done at that moment? Calmly tell Lee we should carefully transition to downhill-mode as gently as possible? Should we have just pointed it downhill with skins on and hope we don’t wreck from downhill skinning? What if we triggered it on the way down? Then we would have all of that snow moving above us and be more likely to be buried and not have a chance to get off the slab. Unfortunately, I don’t have an answer to this question, but I can’t help but think about intuition and gut feelings. They are something you shouldn’t just push away.

We came up with a new game plan to get out of there. It didn’t look like too much hangfire above the crown and maybe we could boot up through some rocks. If the hangfire were to release, it wouldn’t be that big and we would be able to get off of it easier than what we just experienced. Option 1 looked wind loaded with snow and we would have to repeat the same ridge boot pack which was slow and tiring. A week later, there would be a visible crown near this option. Option 3 still felt long and we just wanted to get the hell out of the mountains.

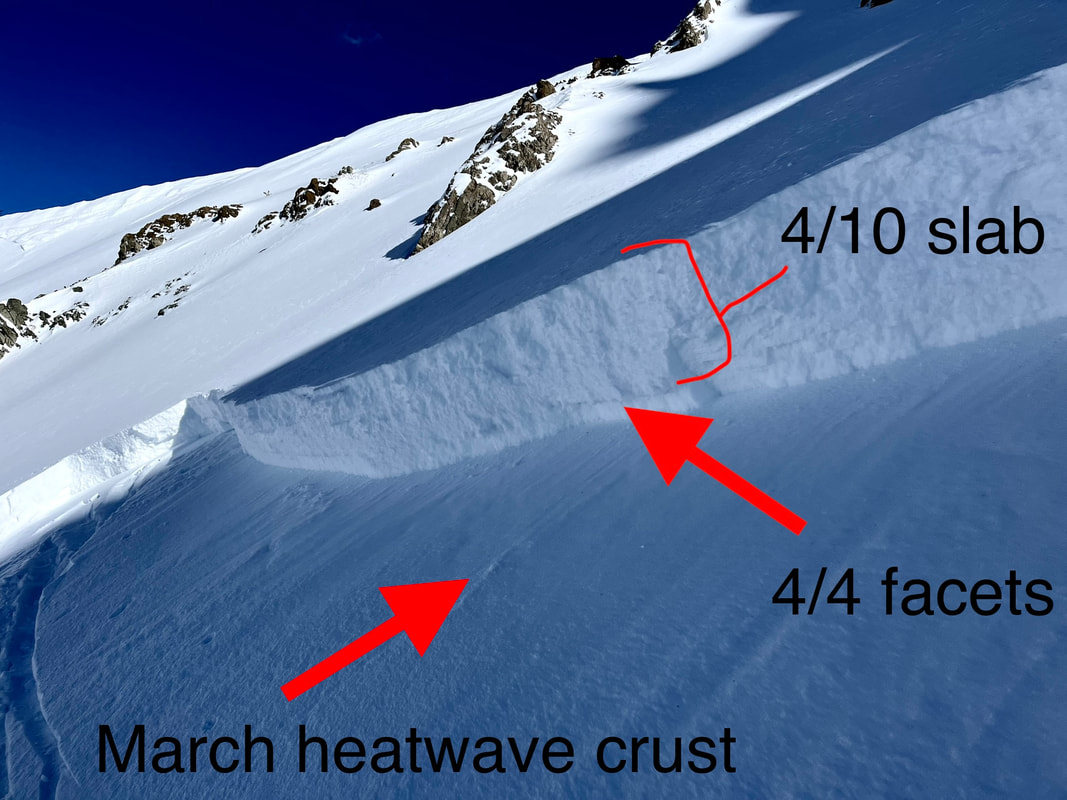

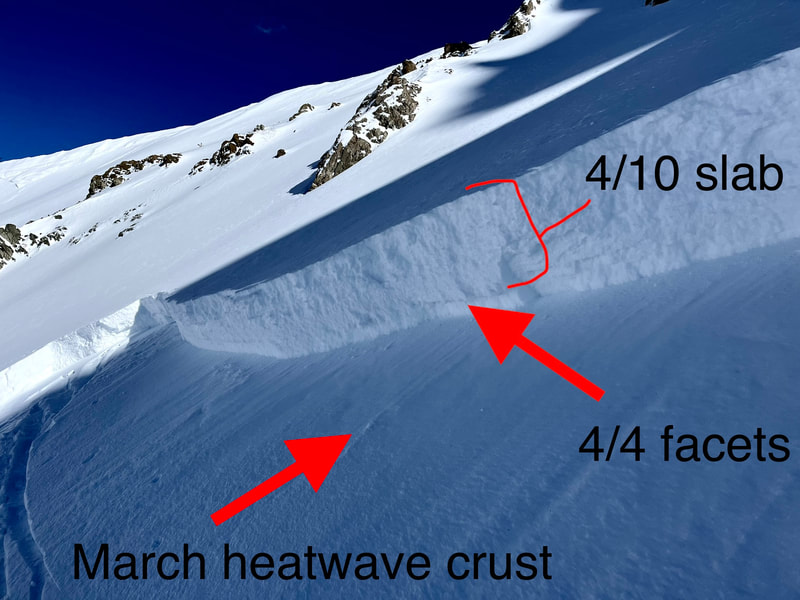

So we skinned up the same slope again. Having to climb it again felt like rubbing salt in the wound. I could feel the facets sitting on top of the bed surface which felt like walking over a slick layer of sand. I would occasionally take video (YouTube Playlist of videos) and photos to document what happened. When we got up to the crown, I ran my fingers through the profile. I visually noted the hand hardness of all the layers and where the failure occurred. There was about a 55cm F->4F soft slab sitting over 5cm of faceted snow 1-2mm, which stood on top of a stout Melt/Freeze crust which formed in a week-long heat wave in March. It was an obvious weak layer that I missed. That sucked. I must have skied over this layer on other slopes within the last week. But now with more snow on it, it had consolidated into a cohesive slab.

I have thought back on that feeling a lot since that day. What could I have done at that moment? Calmly tell Lee we should carefully transition to downhill-mode as gently as possible? Should we have just pointed it downhill with skins on and hope we don’t wreck from downhill skinning? What if we triggered it on the way down? Then we would have all of that snow moving above us and be more likely to be buried and not have a chance to get off the slab. Unfortunately, I don’t have an answer to this question, but I can’t help but think about intuition and gut feelings. They are something you shouldn’t just push away.

We came up with a new game plan to get out of there. It didn’t look like too much hangfire above the crown and maybe we could boot up through some rocks. If the hangfire were to release, it wouldn’t be that big and we would be able to get off of it easier than what we just experienced. Option 1 looked wind loaded with snow and we would have to repeat the same ridge boot pack which was slow and tiring. A week later, there would be a visible crown near this option. Option 3 still felt long and we just wanted to get the hell out of the mountains.

So we skinned up the same slope again. Having to climb it again felt like rubbing salt in the wound. I could feel the facets sitting on top of the bed surface which felt like walking over a slick layer of sand. I would occasionally take video (YouTube Playlist of videos) and photos to document what happened. When we got up to the crown, I ran my fingers through the profile. I visually noted the hand hardness of all the layers and where the failure occurred. There was about a 55cm F->4F soft slab sitting over 5cm of faceted snow 1-2mm, which stood on top of a stout Melt/Freeze crust which formed in a week-long heat wave in March. It was an obvious weak layer that I missed. That sucked. I must have skied over this layer on other slopes within the last week. But now with more snow on it, it had consolidated into a cohesive slab.

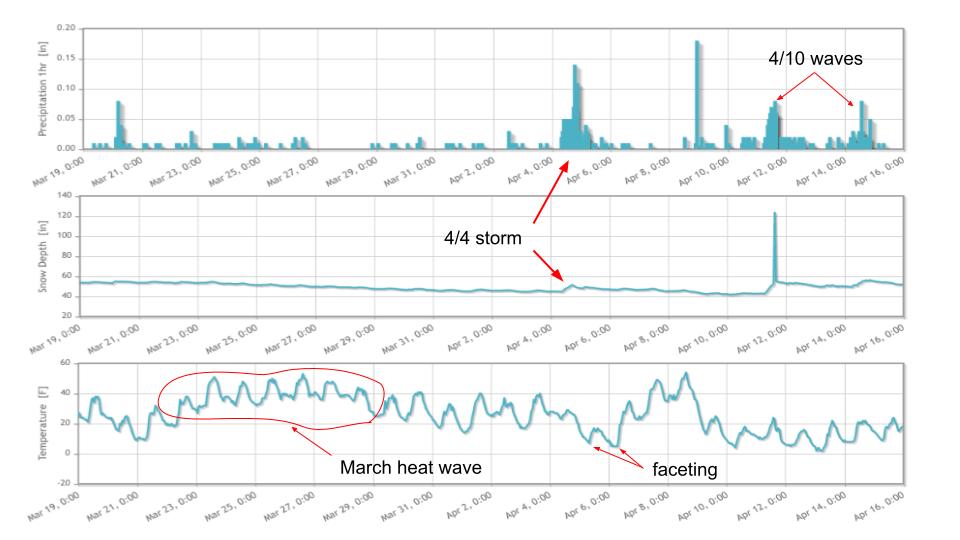

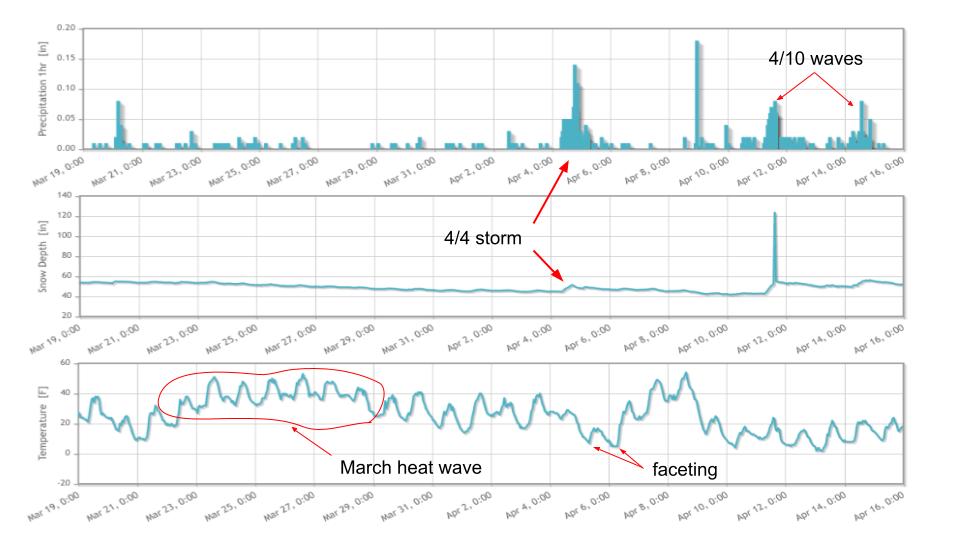

After looking at some nearby weather stations, I put together the pieces that I missed by not digging into the new snow. On April 4, there was a small storm that dropped 4-6” (SWE 0.40-86”) followed by two cold nights where it faceted out. On April 10, that layer was buried by numerous days of moderate increments of snowfall (23-29”, SWE 1.10-2.25”) over a seven day period. These are the perfect breeding grounds for introducing a new weak layer in a time when most of us thought we were just skiing powder in a springtime snowpack (melt freeze cycle).

The snow scientist in me wanted to do some stability tests in a crown profile to see how reactive that layer was and link some corresponding numbers to it. I looked up at what looked like small hangfire from down below and my nerves twitched with the thought of tapping on that slab. We didn’t like our initial plan to boot pack through a small rock couloir, which now looked like 40 feet of tromping over a slab which avalanched less than 30 minutes ago. Lee looked at a rock rib that gave us some more elevation to get closer to the ridge. It would involve skiing 30 feet or so across to another rib of rocks which offered safe passage to the top.

We executed the plan and made it to the saddle. I’ll save you the details as this is already becoming long! We transitioned to skiing and moved quickly through runouts back to our vehicle. The hot spring snow turned back to solid snow (aka breakable crusts) and made for survival skiing.

We executed the plan and made it to the saddle. I’ll save you the details as this is already becoming long! We transitioned to skiing and moved quickly through runouts back to our vehicle. The hot spring snow turned back to solid snow (aka breakable crusts) and made for survival skiing.

So what did I learn? If I want to grow old in the mountains, I will need to increase my margins of safety. This would be easy to do by just avoiding avalanche terrain. But I know this is unrealistic because I enjoy steep skiing. Also, as a ski guide, guests are requesting to go into that type of terrain. So it will require some more thought into how I can manage skiing in steep terrain, but not getting caught in another slab avalanche.

Rules or guidelines work well for me, as I need some hard lines to set in order to actually increase my safety margins. Both times I have now been caught in avalanches when I was skinning. Sometimes there is no other way to get up to the top or through mountains without doing this form of travel. But now I will have to add some more rules to when it’s an acceptable risk to execute in addition to the previously mentioned points. Here are some thoughts I have come up with.

Spacing Out: While skinning up a slope, the team should travel close together and not be lured into “spacing out.” Spacing out is a practice that has never sat well with me, yet I have used it before. It is an idea that dispersing your weight across the snowpack, will lessen the impact on the weak layer. If we are using this method as a safe travel protocol maybe we shouldn’t be traveling on that slope. It is a false sense of security to think you can tip toe over the weak layer in that manner. That is to lower the safety margins to a thin line with disaster.

After being in two avalanches where I was traveling in the uphill mode, it is sinking in that it doesn’t make sense to space out. If we are confident in moving through that terrain, we should be moving together as one unit. Then if something were to go wrong and the slope fails. We would likely be closer to the fracture and have more of a chance to self arrest into the bed surface. There would also be less slab above us and not be buried as deep or carried as far down the path. Now I know that no two avalanche accidents are alike and there might be an instance where it is a hard slab that breaks further above. But I think using this behavior will increase your chances of survival.

Burnout: It was the end of a long season filled with managing a small company through COVID and a low snow year. Between guests and guides getting sick and figuring out where the good snow was after weeks to months of no snow, I was ready to turn the brain off and just go ski some lines. I wasn’t tracking the weather as closely as I should have and wasn’t taking the time to dig, to see what I was missing out there. Burnout comes most years with seasonal guiding work and will have to be taken into account when skiing in the spring. There is no taking “days off” in the mountains. You have to be fully present and be actively reading the current conditions. The day you let your guard down in high risk areas, could be the day the mountains show you their true power.

Winter Returned: I was skiing around like it was a locked-up spring snowpack capped with new snow. Thinking it was glued to that hard crust from the March heatwave. I wasn’t adjusting my mindset (refer to Atkins paper on Ying, Yang, and You) to the fact that it was snowing large amounts with periods of time for weather to change those layers. We had a winter with months of no major change in the snowpack. The 12/11 layer plagued us during the beginning of winter as it was trending towards a Deep Slab in certain locations, but ended up going dominant. After that, we have months of Open Season with no major changes in the snowpack. But then winter turned back on in April and May, so I should have accounted for that change with an Assessment mindset. Whenever it snows, we should be digging in the snowpack to see the new interactions with old snow.

The last point is more of an observation than a lesson. When Lee and I debriefed our incident, he mentioned that he knew he was going to be alright because you had your airbag on. This is a new (to me) concept that I haven't thought about before as a heuristic. Lee was thinking since I had an airbag, I was likely to not get buried and could dig him out. I didn’t ask if he thought this beforehand or if it was only in the moment of sliding down the hill. I can only link this to risk homeostasis, but I don’t think it was a predetermined thought. So I’m not sure if this works in this situation.

Within the coming weeks, the 4/10 persistent weak layer would catch other backcountry travelers off guard. A group of snowmobilers would remote trigger another large avalanche 6 miles north near Phyllis Lake. There was chatter about another group triggering an unreported avalanche in the Sawtooth range. Then a week after, a guided group triggered Cody's bowl while skiing down. Luckily, the guide was able to ski off the slab and the group was posted up in a safe position on the ridge. The guide trusted their gut instinct which told them to make that last turn right towards lower angle terrain. That gut feeling may have been the key to not getting swept down that path.

Sometimes the mountains feel like a drug that is impossible to give up. They allow us to run away from the problems that we face in our real life. As long as we are getting high in the mountains, those problems don’t exist. But even the safest of drugs have shady aspects that require attention, trepidation, and reverence. We have to pay respect to the mountains and in return they will let us come home at the end of the day.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Special thanks to Dan Schwartz for his editing skills and Lee for helping me share this experience with you all. Feel free to write any comments, thoughts, or questions below.

Rules or guidelines work well for me, as I need some hard lines to set in order to actually increase my safety margins. Both times I have now been caught in avalanches when I was skinning. Sometimes there is no other way to get up to the top or through mountains without doing this form of travel. But now I will have to add some more rules to when it’s an acceptable risk to execute in addition to the previously mentioned points. Here are some thoughts I have come up with.

Spacing Out: While skinning up a slope, the team should travel close together and not be lured into “spacing out.” Spacing out is a practice that has never sat well with me, yet I have used it before. It is an idea that dispersing your weight across the snowpack, will lessen the impact on the weak layer. If we are using this method as a safe travel protocol maybe we shouldn’t be traveling on that slope. It is a false sense of security to think you can tip toe over the weak layer in that manner. That is to lower the safety margins to a thin line with disaster.

After being in two avalanches where I was traveling in the uphill mode, it is sinking in that it doesn’t make sense to space out. If we are confident in moving through that terrain, we should be moving together as one unit. Then if something were to go wrong and the slope fails. We would likely be closer to the fracture and have more of a chance to self arrest into the bed surface. There would also be less slab above us and not be buried as deep or carried as far down the path. Now I know that no two avalanche accidents are alike and there might be an instance where it is a hard slab that breaks further above. But I think using this behavior will increase your chances of survival.

Burnout: It was the end of a long season filled with managing a small company through COVID and a low snow year. Between guests and guides getting sick and figuring out where the good snow was after weeks to months of no snow, I was ready to turn the brain off and just go ski some lines. I wasn’t tracking the weather as closely as I should have and wasn’t taking the time to dig, to see what I was missing out there. Burnout comes most years with seasonal guiding work and will have to be taken into account when skiing in the spring. There is no taking “days off” in the mountains. You have to be fully present and be actively reading the current conditions. The day you let your guard down in high risk areas, could be the day the mountains show you their true power.

Winter Returned: I was skiing around like it was a locked-up spring snowpack capped with new snow. Thinking it was glued to that hard crust from the March heatwave. I wasn’t adjusting my mindset (refer to Atkins paper on Ying, Yang, and You) to the fact that it was snowing large amounts with periods of time for weather to change those layers. We had a winter with months of no major change in the snowpack. The 12/11 layer plagued us during the beginning of winter as it was trending towards a Deep Slab in certain locations, but ended up going dominant. After that, we have months of Open Season with no major changes in the snowpack. But then winter turned back on in April and May, so I should have accounted for that change with an Assessment mindset. Whenever it snows, we should be digging in the snowpack to see the new interactions with old snow.

The last point is more of an observation than a lesson. When Lee and I debriefed our incident, he mentioned that he knew he was going to be alright because you had your airbag on. This is a new (to me) concept that I haven't thought about before as a heuristic. Lee was thinking since I had an airbag, I was likely to not get buried and could dig him out. I didn’t ask if he thought this beforehand or if it was only in the moment of sliding down the hill. I can only link this to risk homeostasis, but I don’t think it was a predetermined thought. So I’m not sure if this works in this situation.

Within the coming weeks, the 4/10 persistent weak layer would catch other backcountry travelers off guard. A group of snowmobilers would remote trigger another large avalanche 6 miles north near Phyllis Lake. There was chatter about another group triggering an unreported avalanche in the Sawtooth range. Then a week after, a guided group triggered Cody's bowl while skiing down. Luckily, the guide was able to ski off the slab and the group was posted up in a safe position on the ridge. The guide trusted their gut instinct which told them to make that last turn right towards lower angle terrain. That gut feeling may have been the key to not getting swept down that path.

Sometimes the mountains feel like a drug that is impossible to give up. They allow us to run away from the problems that we face in our real life. As long as we are getting high in the mountains, those problems don’t exist. But even the safest of drugs have shady aspects that require attention, trepidation, and reverence. We have to pay respect to the mountains and in return they will let us come home at the end of the day.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Special thanks to Dan Schwartz for his editing skills and Lee for helping me share this experience with you all. Feel free to write any comments, thoughts, or questions below.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed