I put together the following information to help the public to understand how the new SNRA Outfitter and Guide Management Plan intends to manage Outfitters (Guide Services) within the Sawtooth National Recreation Area (SNRA). I’ve spent days reading through all of the reports and many more hours trying to figure out how this will affect my livelihood that I have been building for over 10 years, in the area I now call home. There are both positive and negative contributions in this plan. We are just now celebrating the 50 year anniversary of the SNRA. While I want to help preserve the protected characteristics of the SNRA (no subdivisions, commercial development, etc.), I also believe as a guide, we are a valuable resource for the SNRA. We help teach the public good stewardship to keep it preserved for future generations. And thankfully this was never turned into a National Park or it would likely look more like Jackson in the Sawtooth Valley!

The following is what I have determined to have a negative impact on myself and the community who wishes to use outfitters to learn more about the outdoors and/or be guided safely through the mountains. It is my hope that I didn’t misread anything or misunderstand the policy that will soon be put in place. If I have made any mistakes, feel free to contact me. I did my best to summarize the plan below:

Priority Use Pool (new additional service days)

At first glance, this new pot of 22,000 service days seems like the Outfitters should be rolling in it! Outfitters won’t be given these days right away (except for the initial allotment, explained next), but they need to EARN them over 5 year increments. And even within those 5 years, there is ONLY a 15% gain allowed (Outfitters with over 1,000 service days). If you do some quick math, that is a potential increase of 150 days every 5 years (from a 1,000 day holder permit). So when a plan is finally determined, Outfitters won’t be graciously given an additional 22,000 days right away. That is a pot that they can dip into over the course of a decade. On the outside, the Priority Use Pool looks like this huge gift to Outfitters, but it comes with a lot of FINE PRINT attached to it.

Initial Allotment Increase

The SNRA will give Outfitters an initial boost of days if they have proven they have needed more in the past or have met their historical use. These additional days will be added to their current permit. That might come from the new Priority Use Pool (Proposed Action) or be in addition to it (Alternative B). The Initial Allotment increase is based on numbers pre-pandemic. We all know there have been more users seeking refuge in the SNRA since prior to 2020.

Depending on the Outfitter’s highest recorded usage in between 2016-2020, will determine which plan is better for that Outfitter. Talk with your Outfitter (Guide Service) and ask them which one will benefit them the most! It seems like the best option to not have additional service days taken from the pot and increase up 50% use of permits from 2016-2020. I recommend the Alternative B alternative to the Initial Allotment Increase.

See document below for my scribbles and notes on this section, as it is a little confusing...

The following is what I have determined to have a negative impact on myself and the community who wishes to use outfitters to learn more about the outdoors and/or be guided safely through the mountains. It is my hope that I didn’t misread anything or misunderstand the policy that will soon be put in place. If I have made any mistakes, feel free to contact me. I did my best to summarize the plan below:

Priority Use Pool (new additional service days)

At first glance, this new pot of 22,000 service days seems like the Outfitters should be rolling in it! Outfitters won’t be given these days right away (except for the initial allotment, explained next), but they need to EARN them over 5 year increments. And even within those 5 years, there is ONLY a 15% gain allowed (Outfitters with over 1,000 service days). If you do some quick math, that is a potential increase of 150 days every 5 years (from a 1,000 day holder permit). So when a plan is finally determined, Outfitters won’t be graciously given an additional 22,000 days right away. That is a pot that they can dip into over the course of a decade. On the outside, the Priority Use Pool looks like this huge gift to Outfitters, but it comes with a lot of FINE PRINT attached to it.

Initial Allotment Increase

The SNRA will give Outfitters an initial boost of days if they have proven they have needed more in the past or have met their historical use. These additional days will be added to their current permit. That might come from the new Priority Use Pool (Proposed Action) or be in addition to it (Alternative B). The Initial Allotment increase is based on numbers pre-pandemic. We all know there have been more users seeking refuge in the SNRA since prior to 2020.

Depending on the Outfitter’s highest recorded usage in between 2016-2020, will determine which plan is better for that Outfitter. Talk with your Outfitter (Guide Service) and ask them which one will benefit them the most! It seems like the best option to not have additional service days taken from the pot and increase up 50% use of permits from 2016-2020. I recommend the Alternative B alternative to the Initial Allotment Increase.

See document below for my scribbles and notes on this section, as it is a little confusing...

| comparison_of_the_alternatives.pdf |

Recreation Report

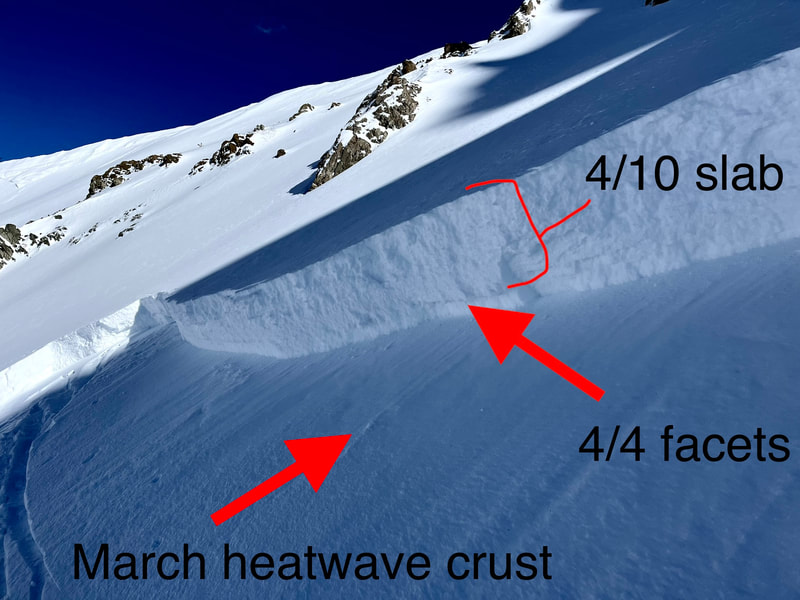

In the Recreation Report, there is no direct evidence or data collected on backcountry skiers or snowboarders who are touring in the Galena Summit area. The SNRA is using public comment and Historical Outfitter days to justify the increased users in the Galena Pass area. They refer to parking being an issue “during and immediately following winter storms, on weekends and during holidays, both the need for plowing and the desire for winter recreation activities is high. This creates challenges and conflicts between user groups as parked vehicles obstruct the ability to plow, limiting parking even further.” I have never personally had an issue with parking up there prior to the pandemic and I visit the pass almost on a daily basis.

All of the numbers documented in the Recreation Report relate to areas the SNRA currently tracks usage. That is the Sawtooth Wilderness (you need to sign a free permit before entering them), select trailheads where it is voluntary to sign in, backcountry huts/yurts, and campgrounds where you have to pay. The Outfitted Public only accounts for 3.5% of the total use according to the figures drawn from the Environmental Assessment.That means there is absolutely no real data collection on anyone who is ski/splitboarding in the SNRA besides the Outfitters who are required to report their usage.

Without the data from the non-guided groups, it is nearly impossible to figure out the carrying capacity (number of people an ecosystem can support without environmental or social degradation) of winter recreation in the SNRA. Winter travel occurs on a renewable surface which is snow. Traveling on snow has no measurable impact on the surfaces below it. The only impacts it has are social (and wildlife) and those are extremely difficult to measure when one isn’t collecting all of the user data out there. It becomes a perceived number based on human memory which often proves to be unreliable.

The Needs Assessment taken during the winter of 2019 revealed that 89% (107 comments) said there was a need for Outfitting and Guide Services on the SNRA. There were 42% (47 comments) that stated they did not think there was excessive use or crowding. There were 75% (82 comments) thought there were places that could support new or additional outfitting and guiding. And lastly, 78% (88 comments) were not concerned about the amount of guiding in the area. Those numbers speak for themselves. The majority of the public comments have expressed the need for more guiding and they didn’t feel like guiding was taking over their areas within the SNRA. I recommend the “No Action” alternative to A12, A18, A19, A26 and 001 design elements.

Wildlife Report

Goats, wolverines, peregrine falcons, Lynx, and others are of concern with increased use. However, outfitters are being cut off areas of concern while the public is able to continue to threaten these areas. This is mainly for over-the-snow vehicles (snowmobiles). I don’t understand how this is acceptable? Whenever I am out guiding a group and realize I am pushing a herd of elk or goats through snow, I change course. I don’t think the public will have the same self enforcement. If there is an area threatened for wildlife, maybe ALL users should be kept out during the breeding season.

Now some of you will think after reading through this that maybe I don’t care about wildlife. I think the mountain goat is one of the most majestic animals out there, I’m jealous of how fast a wolverine can move through the mountains, and that peregrines are an amazing species for surviving the era of DDT. But I don’t agree with how the language is unclear to perimeters of Peregrine closures and how it's only subjecting Outfitters and Guides to being the influence of lowering the number of the Goat, Wolverine, Peregrine species, and others. I recommend the “No Action” alternative to A07, A10, and A16 design elements.

Our Backcountry Huts!

Bob Jonas, Kirk Bachman, and others helped establish a valuable resource of backcountry huts/yurts in our area. The current plan will reduce historical numbers of occupancy at the huts up to 50% reduction (300 nights)! The Plan is also trying to link huts as “wilderness use,” but by regulation, these huts must be placed OUTSIDE the Wilderness Boundary. Some groups never even travel into the Sawtooth Wilderness area. Most groups spend the initial day and last day of their trip just getting into/from the hut, therefore aren’t even accessing the Wilderness area. I recommend the Alternative B plan with the “No Action” alternative to design elements A12, A18, A26, and 001.

Joe St. Onge wrote up a detailed description of the current problems of this plan relating to the huts and yurts of the area. Take a read of his thoughts HERE.

Design Elements

Design Elements are the FINE PRINT that add extra restrictions to the Proposed Action and Alternative B options. I wasn't able to make an image of the Design Elements to be readable on this blog, so you have to download the PDF below.

| Design Elements |

The Rules of Commenting

Upon writing your comments to the SNRA, you are able to pick which of the three options you would like to see in the final management plan. So be specific to which ones you would like to see in there. The options are No Action, Proposed Action, and Alternative B. There are also Design Elements (the fine print!) included in the Environmental Assessment located in Appendix A. The SNRA will be less likely to hear your thoughts if you just COPY/PASTE my information into your letter. So please curate your letter so every vote gets counted!

Comments can be made to [email protected] by August 31st.

Upon writing your comments to the SNRA, you are able to pick which of the three options you would like to see in the final management plan. So be specific to which ones you would like to see in there. The options are No Action, Proposed Action, and Alternative B. There are also Design Elements (the fine print!) included in the Environmental Assessment located in Appendix A. The SNRA will be less likely to hear your thoughts if you just COPY/PASTE my information into your letter. So please curate your letter so every vote gets counted!

Comments can be made to [email protected] by August 31st.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed